I met him only once, in the spring of 2007, though in some respects I felt like I’d known him for many years.

Being a fan is like that.

I’d moved to Charleston less than a year earlier to take a position as a professor at The Citadel, the alma mater of James Oliver Rigney, Jr., the man the world knew as Robert Jordan. Indeed, it was in the biographical blurb on the back of his books that I first heard of The Citadel: for many years, his graduation from the institution was one of the only things I knew about the man.

Jim was already ill when we met. He’d announced his diagnosis of cardiac amyloidosis in the spring of 2006. But when I wrote him with an aim to establishing creative writing awards in honor of him and Pat Conroy (The Citadel’s other famous literary alumnus), he was kind and helpful. And in the spring of 2007, when we gave out the first awards to our students, he surprised me by showing up for the presentation. We chatted briefly. He posed for pictures with the award-winning cadets. I met his extraordinary wife, Harriet.

He passed away that fall, on September 16, 2007.

That December, in an email conversation with Pat, I learned that Jim was going to be posthumously inducted into the South Carolina Academy of Authors. “It pains me that such honors must come after his passing,” I replied, “but I’m glad to see them come at all.”

Pat, too, was pleased, though he noted that there were some who weren’t sure a fantasy writer should be accorded such a literary honor. Sadly, that kind of ignorance didn’t surprise me. I’d already had a (now former) member of my own department say that my short stories shouldn’t count as publications because they were in the fantasy genre.

On February 15, 2008, the chair of my department asked if I’d like to attend Jim’s induction ceremony, which was going to be held on the campus of The Citadel on March 8. “If I don’t get an invite I will break in,” I told him in an email. “Wouldn’t miss it for the world.”

My chair laughed.

It wasn’t really a joke.

Just nine days later, I was stunned to be asked to give a short speech at the induction. I was told that because the induction was going to be on our campus—and because he was an alumnus—it was thought that it would be a good idea if maybe a Citadel professor could take part. Since I knew his work, maybe I could give a short speech introducing him to the academy as a man of letters?

“Of course,” I said.

There would likely be a sizable number of attendees, including a great many of his friends and family. I was informed, again, that some folks had been uncertain about giving such an award to a fantasy writer.

February 29, I put together the speech. It was relatively easy to write, though I already felt that it would be one of the hardest I’d ever have to deliver. How could I encapsulate the man and the writer, while defending the fantasy genre …all in the presence of those who’d loved him most and just lost him from their lives?

March 8 came the event. You can watch the speech in two parts (Part One and Part Two and Gods I was young then!), or you can just read it:

Fantasy and the Literary Legacy of Robert Jordan

Hwæt. We Gardena in geardagum,

þeodcyninga, þrym gefrunon,

hu ða æþelingas ellen fremedon.

These are the first three lines of Beowulf, the oldest—and perhaps still greatest—epic in the English language, a story of mere-creatures come from the mists to terrorize the pre-Viking Danes, of a vengeful dragon threatening the very existence of a nation, and of the one man of incomparable strength who must fight them all. Beowulf is, in a word, Fantasy.

When the monstrous Green Knight stoops to retrieve his own head from the stone floor of King Arthur’s court, when he holds it out before the terrified, astonished, and brutally ignorant knights and ladies, when it speaks, we know Sir Gawain and the Green Knight for the Fantasy that it is.

The tale of Geoffrey Chaucer’s delightful Wife of Bath is nothing if not a Fantasy. So, too, the tale of his Nun’s Priest.

To the realms of Fantasy belong the fairies both noble and nefarious in Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream, the spirits of his Tempest, the witching sisters of his mighty Macbeth.

Virgil’s Aeneas under the onslaught of vindictive gods; Spenser’s Redcrosse Knight and the serpent Error; Dante’s descent through the terrors of the Inferno; Tennyson’s Idylls of the King; Homer’s heroes at the gates of distant Troy: all of them, Fantasy.

Despite this kind of history—a history of literature itself, I daresay—there has been an unfortunate tendency to belittle Fantasy in our modern world. Talking about this problem, George R. R. Martin, himself a writer of Fantasy, is reported to have quipped “that fiction reached the parting of the ways back with Henry James and Robert Louis Stevenson. Before that, there weren’t any real genres. But now you’re either a descendant of James … a serious writer … or a descendant of Stevenson, a mere genre writer.” Martin’s differentiation is perceptive: one needs only to step into Barnes & Noble to see the separation between the Jamesian “serious” stuff—it’s labeled “Literature” and includes luminaries such as Danielle Steele beside Fitzgerald and Hemingway—and the Stevensonian “mere genre” stuff, which is variously labeled “Horror,” “Science Fiction,” or “Fantasy”.

This is a strange fate for genre fiction, though, especially given that in their time James and Stevenson were the very best of friends, and that they recognized the truth shared in their work, divergent though it was in form. It is stranger still given the fact that Fantasy, at least, is arguably the oldest, most widely read mode of literature. From the Epic of Gilgamesh to the Nibelungenlied, it would be difficult, if not impossible, to find a genre that has done more to shape the very thinking of the human species. As Professor John Timmerman describes it: “Fantasy literature as a genre has the capacity to move a reader powerfully. And the motions and emotions involved are not simply visceral as is the case with much modern literature—but spiritual. It affects one’s beliefs, one’s way of viewing life, one’s hopes and dreams and faith.” J.R.R. Tolkien, writing in defense of the genre he had chosen for commenting on our own, all-too-real, perilous world, states that “Fantasy remains a human right: we make it in our measure and in our derivative mode, because we are made: and not only made, but made in the image and likeness of a Maker.”

And so to James Oliver Rigney, Jr., whose works—whose Fantasies—have sold more than 30 million copies, in 20-some languages, all around the globe. These incredible numbers speak for themselves: writing as Robert Jordan, he has been one of the most popular modern Fantasy writers, a verifiable master of that most difficult but impacting of genres, an American heir, it has been said more than once, to the legacy of Tolkien himself. As Edward Rothstein noted in a glowing review in The New York Times (1998): “The genre’s … masterworks by Tolkien, who fought in World War I, were begun on the eve of Britain’s entry into World War II and are fraught with nostalgia. Jordan, the Vietnam vet, is creating an American, late-20th-century counterpart. … where nostalgia is replaced by somberness. … It is as if, in the midst of spinning his web, Jordan has turned fantasy fiction into a game of anthropological Risk, played out in the post-modern age.”

There is nothing simple, nothing small, in this work. The Wheel of Time is the height of seriousness, a vision that cuts to the heart of our cultural, political, and religious worldviews in the way only a Fantasy can: it is not in the mirror, after all, that we see the truth of ourselves; it is in the eyes of strangers in unfamiliar lands.

Rigney revitalized a genre edging on stagnation. He changed the publishing landscape. His influence on this and future generations, measured in the fullness of time, will be nothing short of enormous. 30 million copies. Over 20 languages. And still more to come.

But, truth be told, I don’t think it’s the numbers that are important. Literature is not a popularity contest. It’s something more. Something far more difficult to define. It is sweep and song, power and possibility. It is more about influence on a personal level than it is about bestseller lists and reviews in The New York Times. So I hope you’ll indulge me for another couple minutes to say something more personal.

I was an avid reader in 1990, just entering high school, when I walked into a bookstore in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and saw, just there to my right, The Eye of the World, the first book in The Wheel of Time, a new Fantasy series by an author whose name I did not recognize. It was a trade paperback, a bit more expensive than I would have liked, but I picked it up and stood in the aisle to read a page or two just the same. The words I read were these:

The Wheel of Time turns, and Ages come and pass, leaving memories that become legend. Legend fades to myth, and even myth is long forgotten when the Age that gave it birth comes again. In one Age, called the Third Age by some, an Age yet to come, an Age long past, a wind rose in the Mountains of Mist. The wind was not the beginning. There are neither beginnings nor endings to the turning of the Wheel of Time. But it was a beginning.

I was, in those few lines, hooked. I took the book and my crumpled bills to the counter. I bought it and read it on the bus, every day, for the next few weeks. Soon enough my friends were reading it, too, and they joined me in anxiously awaiting the sequels over the years. I own 11 of those 30 million copies. I am one of Jim’s millions of readers worldwide. And, like many of the others, I can say that I owe much to the experience of consuming his words, his world, his Fantasy. Even if my own fiction career, inspired by his, amounts to little enough, I can say I owe my job here at The Citadel to him: Jim was a proud graduate, and it was within the “About the Author” statement on his books that I first heard the name of this institution, a place of such apparent mystery and mystique that it was the sole bit of biographical information to make it to the back flap of most of his books.

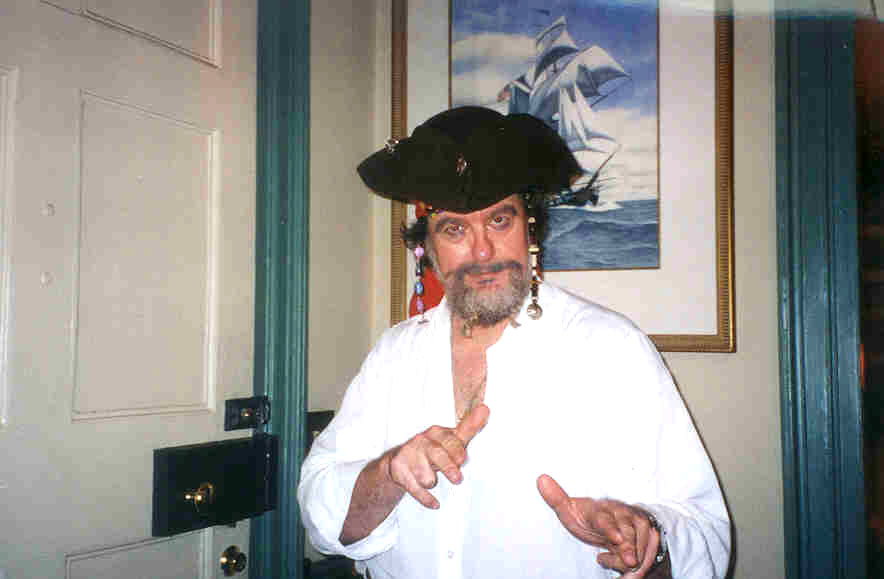

This past spring I had the surprising opportunity to meet him in person at last. Though in poor health, he was nevertheless warm and funny, passionate and giving. I have in my office a photo of him that evening: he’s wearing a dashing black hat on his head, talking to me and some cadets. Looking at the photograph, I cannot help but smile at the way that we are, all of us, riveted on what he is saying. If my memory serves, the moment captured was his declaration that writing Lan, a deeply impressive character in his Wheel of Time series, was easy: “Lan is simply the man I always wished I could be,” he said. Though I knew him for far too short a time, I do not think Jim gave himself the credit he deserved.

Tonight I am most glad that some of that much-deserved credit is at last coming to rest.

If you watch the video carefully, you’ll see that I couldn’t look at the front row for fear that I’d break into tears at the sight of Harriet and his family. I was more nervous than I could imagine.

Little did I know it, but that night was the beginning of a friendship with Harriet and the rest of Team Jordan. Not long afterward, I was giving talks on Jordan here and there and everywhere.

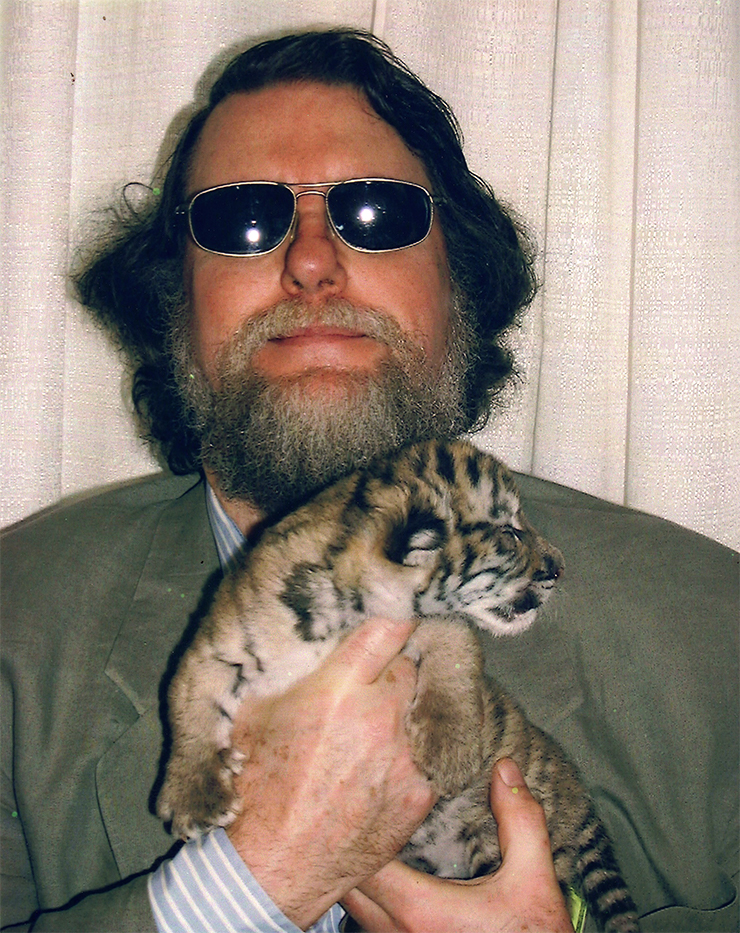

One of those speeches was about how Charleston, settled between its Two Rivers—the Ashley and Cooper—weaves in and out of Jim’s work. Ogier Street. The White Tower on The Citadel campus. The chora tree on Johns Island. The twin dragons on his own front gate. And it took only a few minutes in his office, as I stared up at a saber-tooth tiger skull, to realize that I stood in the middle of the Tanchico Museum.

It was on that same visit to their home that Harriet first told me about Warrior of the Altaii, the sold-but-still-unpublished work that in so many ways gave us the Wheel of Time. She spoke of it in awe and gladness, as she did of her husband. Warrior had been ready to go, she told me, but the chances of fate had led to its being preempted in favor of other books. As the Wheel of Time became a global phenomenon, they’d come to view Warrior as a kind of secret charm: the book was sealed away, radiating good fortune through the years.

Buy the Book

Warrior of the Altaii

I remember my thrill at the prospect that an unpublished work of Robert Jordan’s might exist. I’ve studied his worlds, after all, whether I’m looking at them through the lens of literature or military technology or simply as a fan. What could a new book tell us about his evolution as a writer? Would it be more Conan or more Wheel? Had he reused bits and pieces of it in his later work?

I cannot have been alone in my joy when I heard that the book would finally be released and the answers to these and many more questions might soon be at hand.

Between the release of Warrior and the coming Wheel of Time TV series, the world will soon be seeing much, much more of Jim’s creative legacy. And I, for one, could not be more pleased.

Michael Livingston is a Professor of Medieval Culture at The Citadel who has written extensively both on medieval history and on modern medievalism. His historical fantasy trilogy set in Ancient Rome, The Shards of Heaven, The Gates of Hell, and The Realms of God, is available from Tor Books. His new fantasy novella “Black Crow, White Snow” was released on Friday, May 3rd as an Audible Original.